Introduction the

Tabla vs. Pakhawaj – Complement or Conflict? A Deep Dive from Sangeet Bhushan-2, When one thinks of Indian classical percussion, two iconic instruments come to mind—the Tabla and the Pakhawaj. Both occupy a revered space in Hindustani music, yet they represent two different eras, aesthetics, and approaches to rhythm. Sangeet Bhushan-2, a well-regarded treatise on Indian music, sheds light on the relationship between these instruments. The central question often asked is: Are the tabla and the pakhawaj rivals, or do they complement each other?

The answer, as we will see, is nuanced.

Historical Context

The Pakhawaj is the ancestor of the tabla. A barrel-shaped drum played horizontally, it was the main percussion instrument of Dhrupad, the oldest surviving genre of Hindustani classical music. The pakhawaj’s powerful, resonant sound suited the grandeur and spiritual gravitas of temple and court performances.By contrast, the Tabla emerged in the 18th century, often attributed to the legendary musician Amir Khusro, though scholars debate this claim. What is certain is that the tabla evolved to meet the rhythmic needs of Khayal, Thumri, and later light-classical and popular genres, where delicacy and improvisational finesse were more valued than sheer power.

A lesser-known fact noted in Sangeet Bhushan-2 is that, for a time, both instruments coexisted on the same stage—pakhawaj for dhrupad singers, tabla for khayal singers. This duality shaped the way North Indian classical music developed its rhythmic identities.

Technical Comparison

Construction

- Pakhawaj: A large, barrel-shaped drum made of wood, with both ends covered by parchment. The left side (bayan) produces deep bass, while the right (dayan) produces sharp treble tones.

- Tabla: A pair of small hand-played drums—the right-hand dayan (made of wood) and the left-hand bayan (often metal or clay).

Playing Style

- Pakhawaj strokes are broad and powerful, often played with the whole palm or hand.

- Tabla strokes are precise and intricate, employing fingertips for delicate articulation.

Sonic Quality

- Pakhawaj: Deep, resonant, meditative.

- Tabla: Sharp, versatile, expressive.

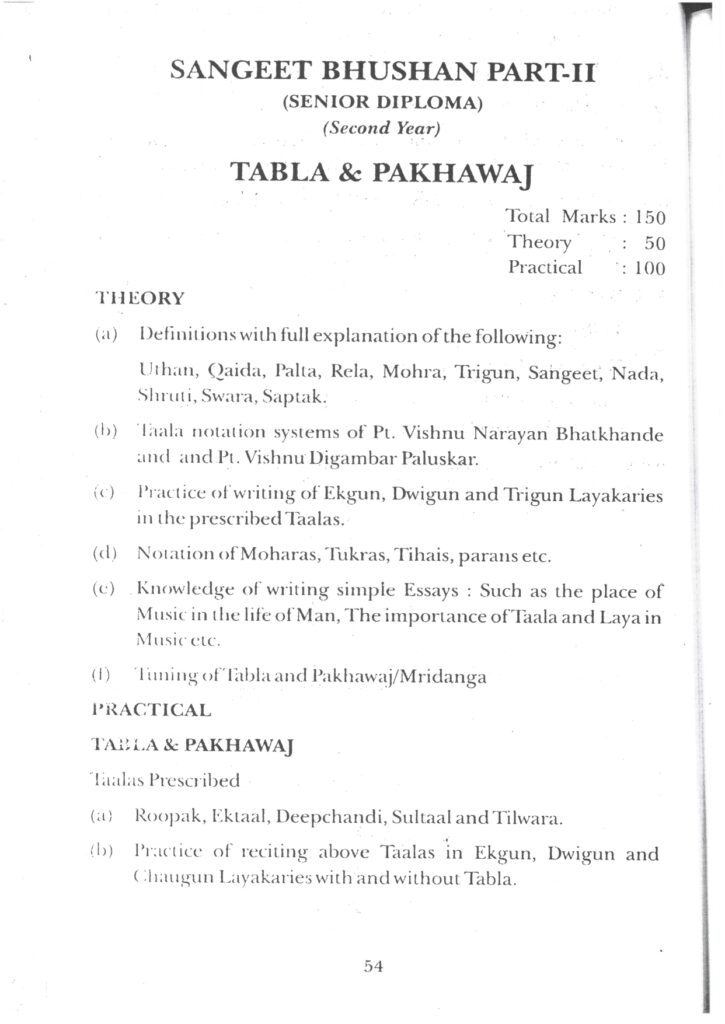

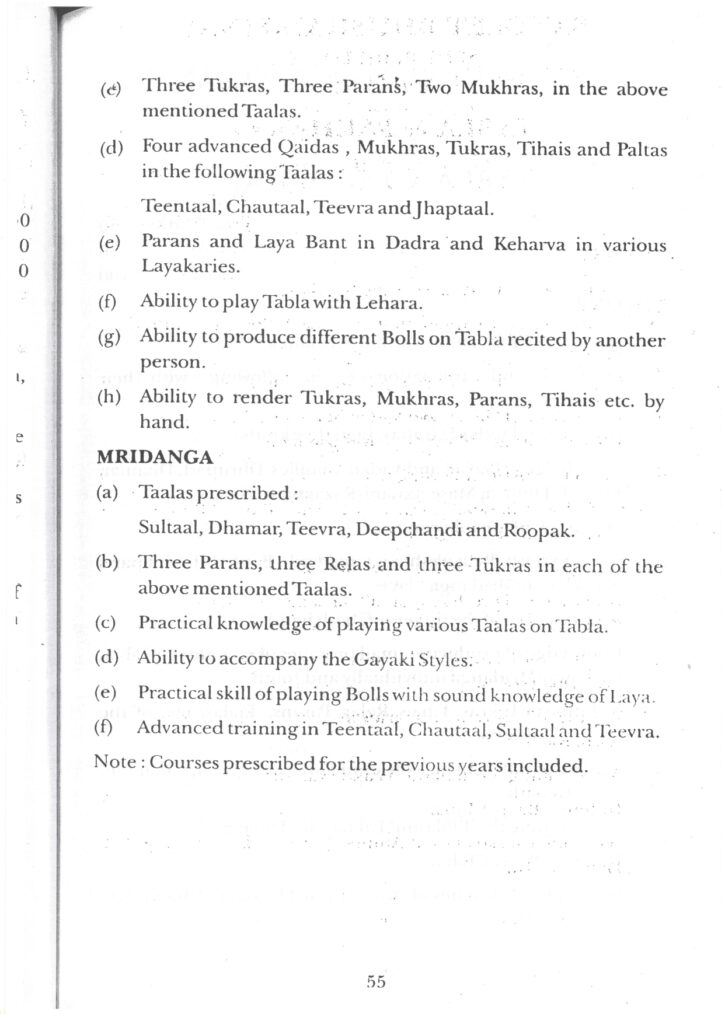

Rhythmic Patterns (Taal)

Both instruments are rhythmic guardians, but their approach to taal differs:

- Pakhawaj is central to taals like Chautaal (12 beats), Dhamar (14 beats), and Sooltaal (10 beats). These are older, symmetrical, and majestic cycles.

- Tabla, on the other hand, excels in taals like Teentaal (16 beats), Ektaal (12 beats), and Jhaptal (10 beats), which are more varied and flexible for improvisation.

In practice, pakhawaj is like a grand temple bell, while tabla is like a finely tuned clock—each vital, but in different contexts.

Famous Performances and Maestros

- Pakhawaj legends include Pandit Purushottam Das, Raja Chatrapati Singh, and Pandit Mohan Shyam Sharma.

- Tabla maestros such as Ustad Zakir Hussain, Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, and Pandit Kishan Maharaj brought the instrument to global prominence.

Interestingly, modern jugalbandis (duets) sometimes bring tabla and pakhawaj together—demonstrating not conflict, but dialogue between the ancient and the modern.

Popular Songs and Recordings Featuring Tabla & Pakhawaj

- Pakhawaj continues to dominate Dhrupad recordings by the Gundecha Brothers, where its weighty bols anchor the meditative alaap.

- Tabla finds its place in both classical and popular music, from Kishori Amonkar’s Khayal renditions to Bollywood hits like Mohe Rang Do Laal (Bajirao Mastani, 2015), where the tabla provides lyrical rhythmic texture.

- In fusion, albums like Shakti (John McLaughlin & Zakir Hussain) demonstrate how tabla has crossed genres.

Cultural Impact

The tabla has undeniably become more ubiquitous than the pakhawaj in the modern era. In concerts, Bollywood, fusion, and even global jazz collaborations, the tabla is the first-choice Indian percussion instrument. Yet, the pakhawaj has retained its niche dignity—preserving the spiritual depth of dhrupad and dhamar.

A survey by the Sangeet Natak Akademi (2021) revealed that tabla students outnumber pakhawaj learners nearly 10 to 1. Still, connoisseurs argue that learning pakhawaj first gives a stronger foundation in rhythm, as its bols are the root of tabla compositions.

As musicologist Dr. Prem Lata Sharma once said:

“The pakhawaj is the ocean; the tabla, its flowing river.”

Interactive Corner

Mini Quiz:

- Which instrument is traditionally associated with Dhrupad?

a) Tabla

b) Pakhawaj - Who is considered the father of modern tabla playing?

a) Ustad Zakir Hussain

b) Amir Khusro - Which taal is a hallmark of Pakhawaj repertoire?

a) Teentaal

b) Chautaal

(Answers: 1-b, 2-b, 3-b)

Poll:

👉 What do you prefer to hear live?

- The thunder of the Pakhawaj

- The versatility of the Tabla

Conclusion

The debate of “Tabla vs. Pakhawaj” is less about conflict and more about context. The pakhawaj embodies tradition, solemnity, and spiritual grandeur. The tabla represents adaptability, intricacy, and modern appeal. Rather than rivals, they are complementary voices in the larger symphony of Hindustani music.

As Sangeet Bhushan-2 wisely observes, “The river may flow ahead, but it never forgets its source.” The tabla’s brilliance owes much to the pakhawaj, and together, they ensure that rhythm remains the eternal heartbeat of Indian music.

👉 If you’ve never heard a pakhawaj live, add it to your musical bucket list—it’s an unforgettable experience. And the next time you tap along to a tabla beat in a song, remember that its roots lie in the mighty resonance of the pakhawaj.

https://www.youtube.com/@BhagawanSingh

https://www.facebook.com/shreebhagwan.singh.904